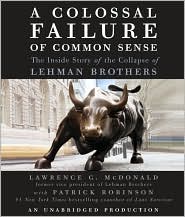

We expected it--the flood of post-crisis commentary, critiques and books on what happened, who was at fault, and how it may happen again. One book chronicled the implosion of Lehman Brothers. At first, it appears to be just another account of the financial bubble and ensuing collapse, as told by a Lehman vice president, Lawrence McDonald. (The book, "A Colossal Failure of Common Sense," eventually made New York Times best-selling lists.)

We expected it--the flood of post-crisis commentary, critiques and books on what happened, who was at fault, and how it may happen again. One book chronicled the implosion of Lehman Brothers. At first, it appears to be just another account of the financial bubble and ensuing collapse, as told by a Lehman vice president, Lawrence McDonald. (The book, "A Colossal Failure of Common Sense," eventually made New York Times best-selling lists.)And one wonders what unique story, inside information or special insight a mid-level VP might have about the demise of one of Wall Street's most storied names. McDonald was a distressed-debt trader at Lehman for only four years.

But with the help of a ghost writer, the book offers an abundance of drama about Lehman going under--from the vantage point of the trading room. The trading room of a major investment bank is its heartbeat, its eye of the storm or its center of all market activity. The trading room is noisy, bustling, frantic--almost the size of a football field. McDonald had a ring-side seat and tells a story of disappointment, defeat, and despair. There is suspense, even when we know the ending.

There is, nonetheless, a disturbing aspect to his story. The subject of diversity and the indifference those on the trading floor had to inclusion and to reforming a culture that was once centered around white males.

McDonald tells how Lehman's president Joe Gregory was fixated on diversity. "He was consumed by it," he writes. Gregory would have diversity assemblies, and he would preach diversity "as if we were running a friggin' prayer meeting."

McDonald suggests Gregory might have been too focused on topics related to culture, recruiting, and inclusion and not sufficiently focused on the firm's exposure to risks or its overblown balance sheet.

Lehman in its last years made admirable progress in at least trying to create a culture of inclusion, recruit people from under-represented groups, and make a public statement about its commitment to diversity. (Lehman regularly hired many Consortium graduates each year and had begun talks to become a bigger supporter.)

Lehman may have failed because of hubris, a disregard for risk management or an overly leveraged balance sheet. But it didn't fail, because it decided it needed to get with the times on the diversity front.

McDonald says those on the trading floor at Lehman ("down in the trenches") dismissed all the fanfare about diversity: "The whole scenario really bothered a lot of people, especially hard-nosed traders who, after hours of real stressful work out there fighting the world, were then being marched off to these meetings and rallies to support (Gregory's) trumpet call for equality."

He goes on: "(Gregory's) mission for diversity drove (a senior research analyst) mad. She had no time for any of it....Most of (the traders) didn't care about the cause...."

Elsewhere in the book, when Lehman appointed Erin Callan CFO in 2008, he describes how colleagues deduced she was selected in part because of (Gregory's) "devotion to underdogs and minority groups."

McDonald provides a convincing account and argument for why Gregory and CEO Dick Fuld should be blamed for Lehman's collapse or for not selling the firm sooner when they had a chance. He shows how they insulated themselves from the rest of the firm and were not competent enough to understand the risks of a market bubbling over or a balance sheet shackled with debt.

Those are likely reasons for Lehman's failure. But a firmwide campaign to embrace inclusiveness wasn't. Diversity is about respect for the talents of all and a spirit that all are competent and can contribute. It's not, as McDonald's traders were suggesting, a wasteful time commitment at the expense of other important corporate objectives.

McDonald's portrayal proves a couple of things, known to many people all along:

(a) With such common attitudes in the trading room, it's easy to understand why it has been difficult for people of color and women to penetrate the tight circles on trading desks, a circle closed in part because of the enormous amounts of money that can be made and shared by few.

(b) Senior management at many top firms has done an admirable job in committing resources and personnel to manage diversity and inclusion, but there is still a lot of work to be done in the trenches (trading floors, deal rooms, research offices, etc.). Lehman had gone so far as to threaten traders' bonuses if they didn't wise up to the firm's diversity mission, but traders were still reluctant to embrace it or go along.

While McDonald apparently sided with the traders and, like them, grew tired of Lehman's growing emphasis on diversity, it probably worked out well for him to have spelled out these scenarios to remind all that there is still work to be done in those trenches.

Tracy Williams

No comments:

Post a Comment